Make or break in World War I

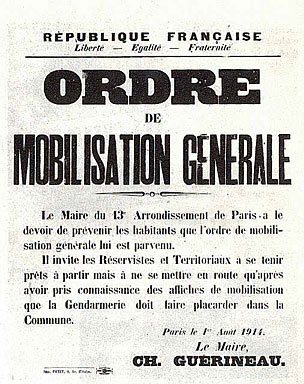

Frank Woolworth spent the early summer of 1914 inspecting his new British stores. At the end of July he was joined by his wife Jennie. Against the advice of his New York office, he arranged a short holiday in Paris as the prelude to a buying trip around continental Europe. He was confident that the political situation would soon calm down and saw no need to disrupt what had become an annual trip.

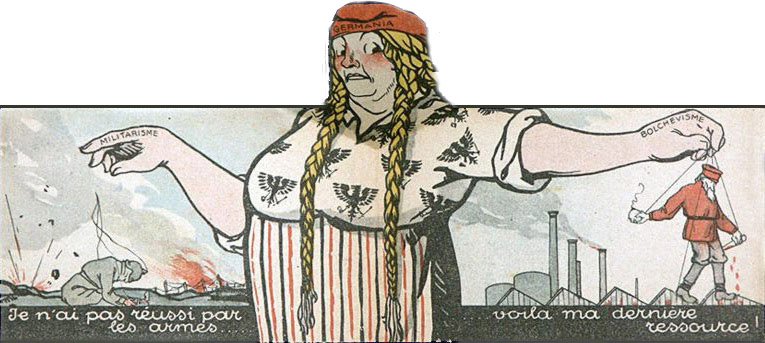

As their limousine pulled into the suburbs of Paris, it was clear that something was wrong. Armed men were being drilled in the streets. All the talk was of war. Would Kaiser Wilhelm invade Belgium or would the Belgians accede to his demands? How safe would the French Republic be if Belgium fell?

In the days that followed Frank Woolworth wrote to his executives in New York each day. His letters reveal the speed of the German advance. The invaders quickly seized control of a large swathe of Europe, leaving Frank with no way back home. Frantic steps were required to secure a safe passage out of France. Woolworth describes a white-knuckle ride as he and Jennie slipped through the enemy lines to secure a passage to the UK, and a cabin on a transatlantic liner.

Although the Germans stopped short of hand-to-hand combat in Paris, hotels and public buildings were converted into makeshift hospitals, with wounded soldiers everywhere. As the Woolworths made their way to Switzerland, using papers hastily arranged by Executive Office in New York, and more than a few francs to smooth the wheels, they found the destruction awesome.

Although the Germans stopped short of hand-to-hand combat in Paris, hotels and public buildings were converted into makeshift hospitals, with wounded soldiers everywhere. As the Woolworths made their way to Switzerland, using papers hastily arranged by Executive Office in New York, and more than a few francs to smooth the wheels, they found the destruction awesome.

Buildings had been destroyed, large swathes of countryside were ravaged, while the roads were filled with migrants fleeing the fighting, dragging their worldly goods in handcarts. German soldiers seemed to be everywhere. Frank had picked up a smattering of French and German, and told officials that he was an American and that he had big factories in Germany and France and that the 5 and 10 was well known as a wealth-generator and a good payer.

The Americans did not join the War until 1917. At the outbreak President Woodrow Wilson called the conflict "the European War" and told the world that his country would remain neutral, though US firms did supply munitions to Britain and Canada.

As Frank set foot on dry land in New York after the arduous journey, he was moved by how normal everything appeared. The contrast to the dreadful scenes that he had witnessed in Europe was stark. Most Americans only became aware of the horrors across the Atlantic three years later.

Empire Room,

New York Office.

MONDAY, OCTOBER 5, 1914. At last we are safe and sound in good old New York. Our boat landed at 6 p.m. Saturday and we were met at the pier by our daughters and sons-in-law and several other friends who were glad to see us.

Now we seem to be in a strange country after such a sad experience the past two months. Here we see no soldiers in uniform. We see no wounded soldiers and hospitals and nurses of the Red Cross. Here we see automobiles, street cars and throngs of people, and nearly all with a smile on their faes, instead of that awful sad look of the people we have met the past two months. In short, we are thankful we had no worse time and thankful to get back alive and well.

We shall close this long record of our experiences with this letter and hope we have not tired you out in reading it.

Yours truly,

F. W. WOOLWORTH. (1)

The letter extract above appears by kind permission of Mr Fred Peterson of Owl Antiques Ltd., USA.

Back in the USA, Frank had a much larger challenge. Almost a quarter of his range was European-made. Those goods generated nearly half of the chain's profit. The War soon halted the supply, as German U-boats made the Atlantic corridor impassable. No-one knew that this situation would continue for four years.

Woolworth's North American stores would soon lose their key point of difference as stocks of these fashionable ranges dried up. Frank considered the Five-and-Ten's very survival to be at risk, and dedicated his energies to addressing the threat.

Woolworth sent a barage of letters to the British Admirality. At the time the UK continued to import a variety of manufactured items from the USA to support its war effort. He argued that on the return journey the vessels were empty and could backhaul British goods to the Five-and-Ten. The First Lord of the Admiralty, a certain Winston Churchill who was later to become one of the most famous men of the twentieth century, retorted that most of the vessels were carrying emigrants to the land of the free.

Woolworth sent a barage of letters to the British Admirality. At the time the UK continued to import a variety of manufactured items from the USA to support its war effort. He argued that on the return journey the vessels were empty and could backhaul British goods to the Five-and-Ten. The First Lord of the Admiralty, a certain Winston Churchill who was later to become one of the most famous men of the twentieth century, retorted that most of the vessels were carrying emigrants to the land of the free.

Woolworth offered to source munitions to reduce costs if the First Sea Lord could make an exception. Churchill was unmoved, stating that the more heavily laden the ship, the less manoeuvreable it would be and the more vulnerable to U-boat attack. As a concession, he released all of the goods that Woolworth had already paid for from the dockside and despatched them to New York, but made clear that there would be no more until the war was won.

America remained neutral until April 1917. They were finally spurred to join the Allies by the Zimmerman telegram, which appeared to confirm rumours that Germany was planning an alliance with Mexico. America's participation proved decisive and helped to bring the long conflict to a close.

Woolworth needed to raise his game. His new-found tactics helped to cement his reputation as one of the world's great entrepreneurs. He made it his mission to help American factories to adopt the principles of mass production that he had seen on his visits to Europe. He even helped suppliers to source raw materials.

It had long been a Woolworth policy to visit suppliers' factories regularly. This allowed the Buyers to look out for any bin-ends of products that they could buy cheaply, and also to discover of their competitors were ordering. But it also helped the firm to gather a deep understanding of how goods were made. They frequently shared the learning with new suppliers to boost efficiency and cut costs.

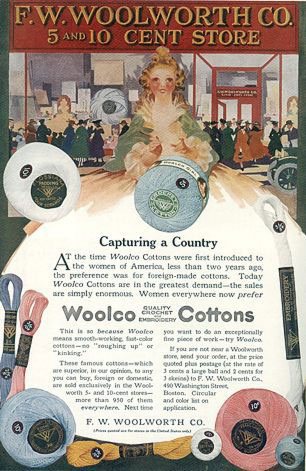

This policy proved invaluable after War broke out. Woolworth and his Buyers toured the USA, armed with samples of items that they wanted their existing suppliers to add to their ranges. They showed engineers how to build the tooling required for manufacture, sourcing the machinery together. Within a year every European item had a new American version. Woolworth's enjoyed particular success with Christmas Decorations (formerly from Germany and Russia), Celluloid Toys (Germany and Switzerland) and Cottons and Needles, which could no longer be sent from the United Kingdom.

As competitors' stocks ran down, the rivals raised their prices. Meanwhile Frank stockpiled his new ranges and then launched them one-by-one. For example he amassed millions of cotton reels, needles and thimbles. Behind the scenes he scheduled a marketing coup. On a specified night he block-booked advertising in the national press for his new all-American range. That night all 900 stores worked late to set up bold prominent displays of the merchandise. The next day customers were greeted by neat, fully-stocked counters and jaw-drop prices. Every product was either offered at the pre-war cost of 10¢ or saw its price fall fifty percent to just 5¢. The advertising attracted millions of inquisitive shoppers, while the price coup captured their loyalty and their cash from his competitors. Despite the price drop, local manufacture had dramatically cut the cost of shipping and handling the goods, meaning that FWW made 1¢ or more extra on every American-made article it sold.

Frank Woolworth's mass-marketing expertise drew attention from the highest in the land, as the US President, Woodrow Wilson, called on him for assistance. The Commander-in-Chief conscripted Frank to his War Cabinet. The retailer was tasked with raising funds and boosting morale. Woolworth had been working on a vanity project, preparing an autobiography with the publicist Bennett Chappell. He did not hesitate, redirecting his aide to join him. Working together the two men developed a savings stamp-based war bond scheme, coining the slogan "a stamp a day for the man who's away". They even persuaded Woolworth's arch-rival Sebastian S. Kresge to take part in the scheme, which saw booths established in-store.

After the Armistice on 11 November 1918 Woolworth instructed that each of his stores was to fly flags and hang bunting. He decreed that the decorations must stay up until every surviving local soldier had returned home. He also encouraged his Managers to use company money to sponsor their local victory parade.

America's entry to the war had proved decisive. Woodrow Wilson's decision to remain neutral until 1917 meant that most servicemen did indeed return home, having avoided the stalemate of trench warfare. The far-away War led to shortages in the USA but disruption to everyday life was quite limited.

Frank Woolworth had lived up to his aspiration to be 'a real live Yankee'. While he had fought on a different battlefield, his victory had helped establish the foundations that saw the United States of America become the economic power-house of the twentieth century, as the country's entrepreneurs finally realised that anything Europe could make, they could build cheaper.

Shortcuts to related content