Working for Woolworth in the 30s

Despite a strict but benign dictatorship in-store, the British company maintained cordial labour relations throughout the 1930s, while in North America the 5¢ & 10¢ boiled over into a hotbed of unrest, as staff demanded better working conditions

High Street Harmony

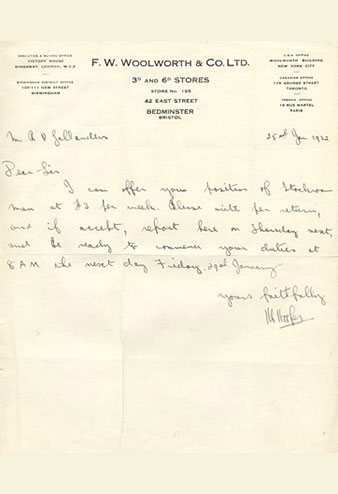

In the Thirties Sales Assistants were paid between 30 shillings (£1.50) and £2 a week. Learners (trainee managers) and stockroom men were paid an extra pound for mobility. They could be moved to another store miles away at very short notice.

In the Thirties Sales Assistants were paid between 30 shillings (£1.50) and £2 a week. Learners (trainee managers) and stockroom men were paid an extra pound for mobility. They could be moved to another store miles away at very short notice.

The chain doubled in size during the decade, which led to plenty of career opportunities. Woolworth demanded a consistent operation in every outlet, whether in London, or on the west coast of Ireland. Store Managers made sure staff were trained and that standards were maintained. The regime was authoritarian but benign. A safety net provided support for loyal workers who were taken ill, or who fell on hard times, but any breach of the rules prompted a stern rebuke.

Many tasks that are automated today were done by hand. For example assistants had to add up purchases in their heads or using 'ready reckoner pads'. Instead of scanning a bar code, they had to record what had been sold in a log and re-order it by filling and posting a form.

To become a 'learner' applicants had to show a good knowledge of every product, its rate of sale and margin. These management trainees also had to command the respect of the staff, and show they could get the job done. The Directors were proud that they had started out by sweeping the stockroom floor and had worked their way up.

Most assistants were young, unmarried women. They rarely kept on working after getting married, instead it was considered normal to get a combined wedding and leaving present. Very few returned to work after bringing up a family. Most staff worked full time, five and half days a week. All had a half-day break midweek, as every store in a town closed early on either Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday.

Assistants were issued with maroon uniforms or stockman's coats, backed by a free laundry service. They were also served a hot lunch which had been prepared by a cook in the staff canteen. They were encouraged to learn about the products they sold. To become a supervisor would have to gain experience on every counter.

A day in the life of a Sales Assistant in the 1930s

In the days before widespread car ownership most store staff walked to work or rode in on a bicycle. The great majority lived within a mile or so of the store where they worked. Typically they set out from home at 8.15am, allowing time for a quick cup of tea in-store before their shift began. They had to don their uniform and to be on the salesfloor for morning inspection at 8.45am, 15 minutes before opening time.

Morning inspection gave the Manager the chance to sharpen the displays, check the availability of best-selling lines and give topical tips for the day's trading. In between serving the customers the Assistant would spend the early part of the day preparing a stock list, which was sent to the stockroom. A Stockroom Assistant would gather the goods into a trolley and take it to the salesfloor. Neither Sales Assistants nor Supervisors were allowed access to the stockroom until many years later.

Lunch breaks were staggered, starting shortly after 11am. The approach helped to keep the store well staffed during the peak hours between noon and 2pm. Most branches employed a cook and a cleaner and provided a hot lunch at a subsidised price. After a brief lull in the early afternoon, the store would be packed again from just after 3pm, as mums and children visited after school. In between serving customers, staff would fill the counter from their stock trolley, prepare orders for any missing lines, and double-check that every item was priced. Each week work built toward the weekend. Stores had to be picture perfect by Friday afternoon. At the time most shoppers got their pay packets each Friday. Some hurried to Woolworth's at once, while most made Saturday their shopping day. Most stores closed at 5.30pm. Staff had to wait on the salefloor until all the customers had left before making their way upstairs to fetch their coats and heading off home. The next day the cycle began again.

Mayhem in Main Street

In North America, President J. Edgar Hoover's New Deal rocked the foundations of the Woolworth 5 & 10¢. It had always kept its costs ultra-low, hiring young clerks on a very low wage. The Founder simply replaced any clerk who became difficult or lazy. He paid "a little extra" to retain the best people, but only if they agreed to start early, work late and "do other chores like window-washing in dull season".

The formula remained consistent for fifty years, Woolworth was slow to add 15¢ and 20¢ lines, which held wages down. The New Deal forced a rethink. The new laws imposed minimum wages in key industries, collective bargaining and empowered trade unions. This gave the staff a voice.

Contrary to corporate PR portraying a happy workforce, press reports of the extravagance of the 'Woolworth Heirs' caused great resentment. The media dubbed Barabara Hutton, Frank Woolworth's granddaughter, 'the poor little rich girl'.

Contrary to corporate PR portraying a happy workforce, press reports of the extravagance of the 'Woolworth Heirs' caused great resentment. The media dubbed Barabara Hutton, Frank Woolworth's granddaughter, 'the poor little rich girl'.

Barbara's mother Edna had died in tragic circumstances when she was a child. At 21 she had received two legacies, one from her grandfather's estate, the other from her late mother's. Her father, Edwin Laws Hutton, got her to cash in her massive stockholding days just before the Wall Street Crash, ending her link to the brand once and for all. Days later investors facing ruin felt cheated by the 'Poor Little Rich Girl'.

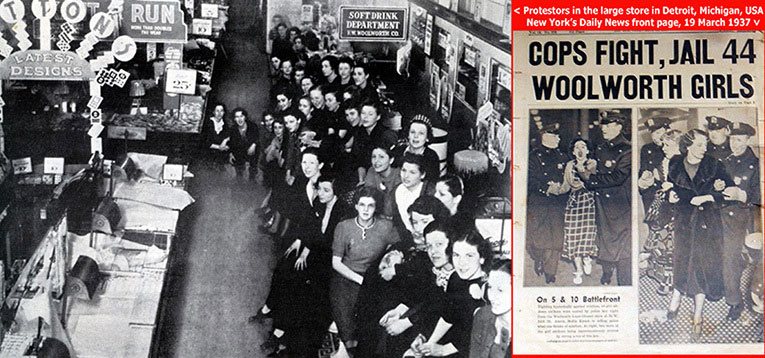

Her parties and love life filled the gossip columns. Stirred up by their unofficial shop stewards, staff couldn't understand why the firm wouldn't pay them $8 a week or recognise the Union when 'the owner' could splurge $21,000 on a frock.

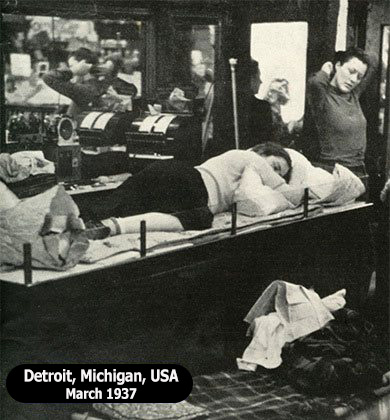

The rage boiled over in March 1937. City centre staff held sit-ins, demading Union recognition and $8 a week. The woes of the 5 & 10¢ girls hit the headlines, beside photos of clerks sleeping on the famous mahogany counters.

The fact that Hutton had no link to Woolworth cut no ice. After dithering the Board caved in. The Union was recognised, hours were cut and a wage increase was phased in to end the strike.

Savings were sought to balance the books. Secret plans were hatched to halve the number of clerks by embracing 'self-selection' at some displays and central cash and wrap desks. Problems were ironed out during trials. By 1945 every new store was self-service, and a rapid project to convert the existing stores began in 1950.

Ironically the increase in wages in the late 1930s ultimately lowered the wage bill. The campaign had won better wages and improved working conditions, but for a much smaller workforce.

Quick Links to related content

1930s Gallery

Openings transform the High Street

Museum Navigation

World War II and its aftermath